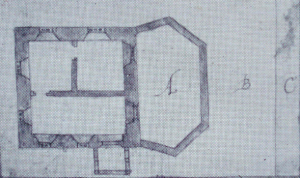

One day in the early decades of the 16th century, the peace of Brownsea Island at the mouth of Poole Harbour was shattered by the arrival of boats carrying men and tools from nearby Poole. They had come to lay the foundations for a fort or blockhouse, part of a string of coastal defences ordered by King Henry VIII. Boat-loads of stone and chalk followed and the blockhouse soon took shape near the landing place overlooking the harbour entrance. It was built on a solid platform and consisted of a single storey square tower around 13m by 13m with walls 2m thick. The guns were to be mounted on the flat roof of the tower. On the eastern side was a barbican or walled courtyard with a perimeter of 18.7m. The tower was surrounded by a ditch with a drawbridge to give access. Inside the building were a large hall and two smaller rooms, lit by small, barred windows. Although the block-house was a royal project, it was the town of Poole which had to organise its construction and provide a gunner, an assistant and three men to operate it.

For over 350 years, the island had belonged to Cerne Abbey which maintained a hermit and chapel there and held the right to any ‘wreck of the sea’ washed up on its shores. It was a quiet backwater, mainly heathland with few trees and little cultivation. Local men occasionally visited to fish, dig ballast and catch rabbits or for more nefarious purposes, but otherwise its peace was rarely disturbed. Now a new, noisier and more contentious era had opened for Brownsea.

Over the next few years guns arrived and were transported over to the island under the direction of the Mayor of Poole. A culverin, demi-culverin and port piece and two sakers with the appropriate iron shot, barrels of gunpowder and other equipment were installed in the blockhouse. The problem was to maintain the fort and guns in good condition and by 1551, the Mayor and burgesses of Poole were petitioning the Privy Council for new cannon and repairs to the blockhouse. Alterations including increasing the height of the tower and the barbican wall cost Poole £133. Again in 1562 Poole petitioned the Privy Council that Brownsea Castle was in disrepair and the cannon unserviceable. This time the maintenance was transferred to central government.

In the meantime, the ownership of the main island also changed. The Abbey of Cerne was dissolved in 1539 as part of Henry VIII’s reformation, and all its properties, including Brownsea, became the possession of the Crown. In 1545, Henry granted the island (excluding the blockhouse) to John Vere, Earl of Oxford who transferred it with Henry’s consent to lawyer, Richard Duke. As clerk to the Court of Augmentations which managed the properties reverting to the crown following the dissolution of the monasteries, Duke was in a good position to acquire many former monastery properties in the West Country.

The new owners saw a way to make money on their acquisition by entering a partnership to work the deposits of ferrous sulphate or copperas found on the island. This mineral was a valuable product used in the dyeing of textiles, tanning and ink-making. A later description of the works by the traveller Celia Fiennes gives an idea of what they looked like to an interested visitor. The nodules of the mineral were laid out on slightly raised sloping beds to dissolve in the rain and the resulting liquor was fed through pipes into the boiling house where large square pans were kept boiling by furnaces. ‘They place iron spikes in the panns full of branches, and so as the Liquar boyles to a candy it hangs on those branches. I saw some taken up, it look’d like a vast bunch of grapes, the coulour of the Copperace not being much differing.’

In 1576, to the consternation of Poole’s leading citizens, Queen Elizabeth awarded the castle at Brownsea to her favourite, Christopher Hatton. He had first come to her notice through his skills as a courtier and was a rising man, rapidly acquiring lands and titles including that of Vice Admiral of Purbeck and Constable of Corfe Castle. The following year he was to be knighted and made Vice Chamberlain and ten years later he became Chancellor, proving to be an impressive statesman with a fine grasp of public affairs. The demands of Hatton’s public duties and almost daily attendance on the Queen, meant that he left his duties in Purbeck in the hands of a deputy, Francis Hawley, based at Corfe Castle. Under Hatton’s sponsorship, Hawley was three times returned as M.P. for Corfe Castle. He was also able to indulge in lucrative sidelines such as doing deals with the pirates who haunted the Purbeck coast. Richly attired pirate captains would come ashore at Studland to sell their stolen goods without fear of the law while Hawley pocketed sweeteners or had his pick of the choicest goods.

Many local people also traded with the pirates including Mr Phillips, the captain or gunner of Brownsea castle. According to a testimony of 1582, Phillips ‘had a monkey, a parrot and sold beer to Captain Heynes’ and stored three tons of Brazil wood for him in Brownsea Chapel and 112 hogsheads of herrings in the castle. Stephen Heynes was a notorious pirate, known to use torture on his captives to force them to reveal the hiding place of any valuables. Four years later, the next gunner, Walter Partridge, was said to have bought 40 pieces of raisins and two bags of almonds from pirates ‘which the said Partridge with others did carry in a boat to Brownsea castle aforesaid in the night season’.

Brownsea was something of a law unto itself and was regarded with suspicion by the people of Poole. In 1586, a man called James Mounsey was sent to Poole by Francis Hawley for some official purpose and the Mayor and Burgesses complained about him in a letter to Hawley. They described Mounsey as a man ‘whose religion we doubt, for that we have not seen him at any time at the Church at the time of his being here. He hath a brother a very bad fellow, and of an odious religion, who serveth in Brownsea mines under him. He persuadeth the workmen there to labour on the Sabbath day and to rest Saturday, which he saith is the Sabbath day. We understand this Mounsey to be indebted to the victuallers of this town and the workmen of Brownsea mines.’

Relations with the gunners of Brownsea had also long been tense. As far back as 1578, John Gobey had complained at the Poole Admiralty Court that a ‘callyber’ [hand gun] which he had found at the bottom of the sea near Brownsea had been taken from him by force by the gunner, Richard Skovell. In 1681, the minutes of the Court reported that ‘the gunner of Brownsea castle doth molest the inhabitants of the town and will not suffer them to pass any persons from Northaven to Southaven Point but doth threaten them to shoot at them and violently doth take their money from them, which is not only a great hindrance to poor men that were wont to gain money that way, but also an infringing of our liberties.’

Worse was to come. On 11th February 1589, Walter Meryet, owner and master of the Bountiful Gifte was sailing out of Poole with a cargo of copperas bound for London. Because of the international situation, the authorities had put a stay on shipping in case vessels might be needed for naval purposes. Any ship wanting to leave port needed a special pass from the correct authorities. Meryet had a pass from the port authorities at Poole and went ashore at Brownsea to present this to the gunner, Walter Partridge. However Partridge told him that this was not good enough and that he needed a proper pass from Francis Hawley at Corfe Castle. Meryet replied that he had sent someone to fetch this pass and pressed Partridge to let him pass. Apparently a similar situation had arisen before between the two men because Partridge again refused, saying that Meryet had caused him trouble before with his master, Mr. Hawley.

Meryet went back on board his ship, but instead of sailing back to Poole, he defiantly set sail for the harbour entrance. Partridge’s response was to open fire. His first shot passed over the ship but the second, according to one witness, fell short, grazed the water and then hit the vessel. Other witnesses reported that Partridge deliberately aimed ‘between wind and water’, in other words, at the vulnerable part of the ship just below the waterline. The shot hit Walter Meryet behind his right knee, shattering his thigh bone ‘fower ynches long on the owt side of his legg’. It also hit crew member William Drake in his right thigh, giving him a six inch wound. After firing, Partidge got up on the wall to try to see through the smoke and asked witness Peter Peers if he had seen the shot. Peers said that it had struck the barque and done some harm to which Partridge replied ‘I cannot help it nowe.’ The two terribly injured men were put on board the Primrose to be taken back to Poole but William Drake died as they came up the channel. Walter Meryet was landed alive at Poole Quay and taken to his house where he died the following day.

Electrified first by the sound of shots across the harbour and then by the news of the deaths, the people of Poole were incensed. An inquest was convened and evidence heard, resulting in a verdict of wilful murder against Walter Partridge. At his trial at the Admiralty Court at Corfe Castle, Partridge was found guilty of manslaughter and condemned to death, being unable to plead benefit of clergy because his offence had been committed at sea. However this was not the end of his story because in December 1590 he received a grant of pardon for the killing of William Drake and Walter Meryet ‘by the glancing of a bullet, which he shot at a ship wherein they were, intending to stay the said ship.’ Obviously his masters Francis Hawley and Christopher Hatton looked after their own.

Around 1597, a map of Brownsea was drawn up with a description giving an idea of what the island was like at the close of the century: ‘Brownesea is a little island lyinge by the channell or going forth betwene Poole and the Isle of Purbeck; the length thereof by his extreames is 411 pertches and at the brodest place is over 206 perches. Yt conteyneth of undrowned lande wheron somthinge greweth 354 acres and 4 rods. The nature of the grownd is drie, sandie and bringeth forth only heath and in some few plases furses. But that there is at the east end of the land about a howse theare about six acres that is greene ground and naturale to bringe forth corne. The lande lyeth very high for the most parte, and into the east parte thereof betwene two hills a creek of the sea doth ebb and flow, and at the hed therof is a percell of marris or moore ground. Upon the southwest parte therof also have ben coperis mynes now decayed. The land doth yeald cunnies [rabbits] and will feede rother cattell, horses and sheep, and the better by the woore [seaweed] cast ashore by the sea.’ From this description it seems that Brownsea was scarcely more developed at the end than at the beginning of the Tudor age.

Jenny

Sources included: A History of Brownsea Island by John Bugler and Gregory Drew / Brownsea Island by Charles Van Raalte / Treasures of the Golden Grape by Selwyn Williams / CI 1 Coroner’s Inquest on Walter Meryet and William Drake (Poole Archives) / Plan of Brunksey (Brownsea) Castle, island, Poole and harbour, and district from Cecil Papers: Miscellaneous 1597 (copy at Dorset History Centre).

Very interesting read!